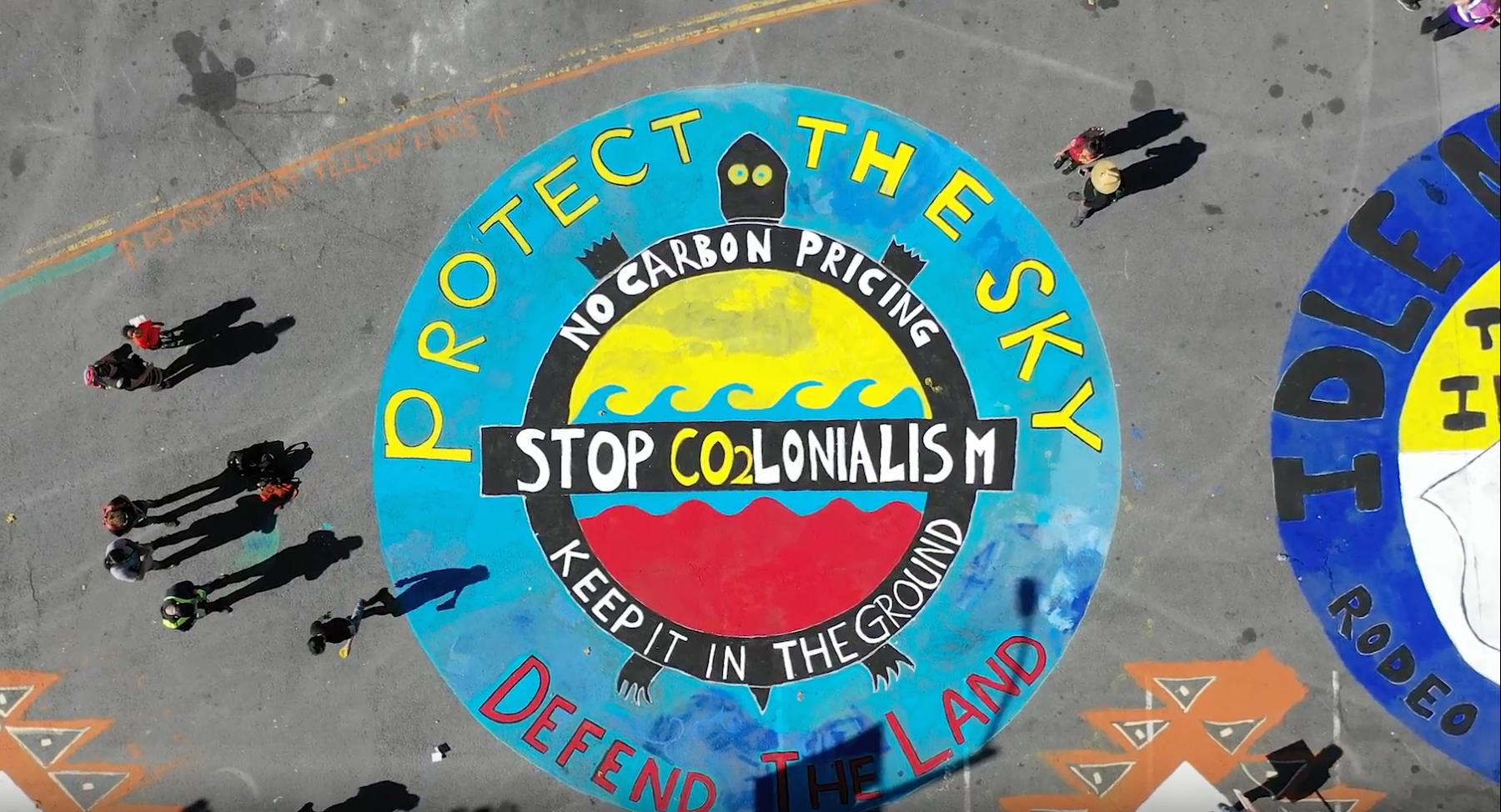

The root causes of climate change are multifaceted and intersectional: namely, resource extraction at a pace exceeding the natural limits of the earth systems, carried out through colonial economies that provide profit for a few at a cost to many. Real solutions must be tailored to tackle root systemic drivers, in addition to being demonstrated through principled practice, to actually work. For a climate justice future, we must move beyond carbon targets (whether parts per million or emissions percentages), because such targets reinforce a carbon reductionist paradigm, which has emerged from Euro-centric scientific discourse and markets-based frameworks that avoid addressing the root causes of climate change.

Addressing root causes entails working with the diversity of place-based needs and available resources instead of seeking “one-size-fits-all,” centralized solutions. Examining root causes allows us to understand how reducing carbon needs to be coupled with efforts to eliminate toxic pollution, biodiversity and cultural destruction, theft and colonization of lands, militarization and authoritarian governments, racialized and gendered poverty and violence. Tackling root causes requires us to first “scale deep,” prioritizing locally-led, locally-designed initiatives; and then “scale out” to facilitate translocal networks of co-liberation, before we can consider “scaling up” in truly democratic and impactful fashion.

Real solutions to climate change must:

- Be guided by principled practice

- Be guided by Indigenous Traditional Knowledge, place-based experience and public-interest science

- Be holistic in tackling all intertwined ecological and social harm

- Replace economies of greed with economies serving ecological and human need

- Advance deep, direct and participatory democracy, rooted in local self-determination

- Center the leadership and needs of those presently and historically most harmed

1. Real solutions must be guided by principled practice.

Real solutions must be guided by principles such as those of environmental justice (EJ),[1] just transition,[2] democratic organizing and energy democracy,[3],[4] which have been articulated and vetted by grassroots environmental movements around the world. By providing intersectional guidelines for transformative change, these principles help us determine “just” pathways to both “decarbonizing the economy” and reducing other forms of environmental harm that have disproportionately burdened historically oppressed communities. These principles help guide climate strategies and solutions that break free from the barriers created by white supremacy culture, reductionist thinking and neoliberal ideologies that lead us astray. In addition to these movement principles, credible climate solutions must adhere to the precautionary principle,[5] prior to any field testing and application. While corporate lobbyists often critique the precautionary approach as a “hurdle to progress,” this science-based guideline should be applied to all new innovation, technologies and practices that are not rooted in Indigenous Traditional Knowledge and local ecological experience.

Examples:

A core value across these sets of principles is that of “nothing about us, without us” or centering the voices, needs and leadership of those most directly and severely impacted.[6] Participatory Action Research (PAR) principles have been developed by movements and their academic allies around the world,[7] with their own sets of principles to guide research and study of locally appropriate solutions centering the voices of those harmed.

An early example of applied PAR are the Barefoot Colleges that were born from South Asia’s struggle against British colonial rule, with the belief that those most historically oppressed needed to be supported with institutions of study and research tailored to their traditional ways of knowing and centering their rights to collective self-determination. After 50 years of experimentation in India, the barefoot college model has spread to over 1300 villages in over 17 countries across Asia, Africa and Latin America.[8]

These principles help guide climate strategies and solutions that break free from the barriers created by white supremacy culture, reductionist thinking and neoliberal ideologies that lead us astray.

2. Real solutions must be guided by Indigenous Traditional Knowledge, place-based experience and public-interest science.

To be able to look into the future to see which solutions are most beneficial, least harmful, durable and equitable, we need to rely on the historic knowledge of humanity’s oldest living memories of how to live in harmony, balance and reciprocity with the Earth and all her children. Centering local Indigenous Traditional Knowledge, wisdom and values allows us the clearest line of sight for tackling the storms, floods, fires, droughts and disease headed our way.[9] Noting that in many parts of the world colonial rule has attempted to wipe out Indigenous Peoples and their knowledge systems, at times we may need to look to settler and migrant cultures that have cultivated subsistence practices rooted in local ecology, and learn from these practices to build living regenerative economies purposed to heal, restore and revitalize our relations with all life. In addition to the place-based wisdom of Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, real solutions must be guided by credible, public-interest research and science, namely science that has strong public oversight and is publicly funded (not influenced by corporate dollars). Finally, to be aligned with a just transition, all colonial states need to seek approval from the leadership, territorial governance and wisdom of Indigenous Peoples, for all climate strategies. And where Free, Prior and Informed consent (FPIC) is applied as a framework for seeking such approval, all FPIC protocols and processes should be determined by the leadership of each Indigenous Nation.

Examples:

For Indigenous Peoples and peasant farmers, agroecology and food sovereignty are key strategies for reducing emissions and realizing social justice.[10] Indigenous Food Sovereignty is a holistic framework that looks beyond the harm caused by industrial, productionist and commodified agriculture, as well as the limitations of settler, colonial farming, to support regenerative practices of fishing, hunting, harvesting and farming rooted in Indigenous Traditional Knowledge, to meet essential food, medicine and cultural needs while protecting and restoring the ecosystems that provide these.[11]

From reversing human-caused desertification around the world,[12] to restoring aquatic ecosystems and wildlife habitat – Indigenous land use practices are critical to restoring the balance between atmospheric and biotic carbon.[13], [14], [15] And as international disaster response agencies continue to fail at tackling the increasing scale and intensity of climate chaos, there is a growing recognition that we need Indigenous Traditional Knowledge to effectively fight the fires, the floods and the droughts.[16]

3. Real solutions must be holistic in tackling intertwined ecological and social harm.

All efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions must be coupled with strategies to reduce toxic co-pollutants, waste and biodiversity destruction, as well as disproportionate pollution and poverty burdens borne by Black, Brown, Indigenous, migrant and poor communities around the world. Real solutions must be guided by our reciprocal relations with all life; aligned with restoring ecosystems and species impacted by the global extractive economy; restoring the health of all species whose wellbeing we depend on for our own.

The climate crisis cannot be tackled without gauging “decarbonization” efforts by their ability to detoxify, decommodify, degentrify, demilitarize, decentralize, decolonize and democratize our economies. Such an integrated approach ensures that harm reduction in one aspect of any process does not exacerbate burdens in another. As such, real solutions need to be holistic in examining the life-cycles of carbon in a broader context of all associated harm, i.e. the proliferation of plastics in our oceans, the depletion of soil nutrition and high COVID-19 mortality in EJ communities due the disproportionate industrial pollution burdens they bear.

Examples:

Zero Waste: In nature there is nothing such as waste, hence efforts to create zero waste systems to reduce, reuse, recycle and compost waste in our cities and towns lighten the human footprint in a variety of ways – from significantly reducing climate and toxic pollution loads to relocalizing the materials economy, while creating millions of new jobs and just transition pathways for the poorest communities.[17] Zero waste strategies, which avoid burning or burying waste, are one of the most affordable ways for cities and communities to transition to local, community-controlled economies.[18]

Public Transportation: The fastest growing source of global greenhouse gas emissions are from the transportation sector, and over 72% of these emissions are from road travel.[19] By relocalizing transportation and reallocating fossil fuel subsidies to serve essential human needs such as housing and healthcare, far more jobs can be created with far less pollution than the status quo. Innovative examples of transportation solutions include the design of walkable cities,[20] like the district of Vauban in Freiburg Germany;[21] and community organizing campaigns such as that of the Los Angeles Bus Riders Union, the Strategy Center and their allies to shift the LA Mass Transit Authority (MTA) towards intersectional transportation goals of Free Public Transportation, No Police on MTA Buses and Trains, Ending MTA Attacks on Black Passengers, No Police in the LAUSD Schools, and No Cars in L.A.[22]

Looking to shift the hundreds of billions in subsidies presently handed to the oil and gas sector, we need to look at the trillions spent on the war industry. While there are few examples of efforts to demilitarize the global extractive economy, campaigns like About Face – Veterans against War, acknowledge that repurposing the lives of hundreds of thousands of young people, from serving fossil fuel corporations to serving humanitarian needs, would help to both save lives and reduce massive amounts of atmospheric carbon.[23]

4. Real solutions must replace economies of greed with economies that serve ecological and human need.

To be effective at doing so, real solutions need to be part of a suite of just transition strategies that move us towards local, regenerative economies guided by caring, sharing, solidarity and mutual aid.[24], [25] There are thousands of active experiments around the world, providing emergent lessons from efforts to build a solidarity and feminist economy, from timebanking and trans-local community investment assistance, to federations of worker-owned cooperatives such as Mondragon in the Basque region of Spain.[26]

Often, the best places to find such holistic analysis are at the intersections of the oldest struggles, amidst some of the poorest, most marginalized communities – where people continue to struggle against racialized poverty, resource wars, forced migration; as well as the onslaught of hurricanes, forest fires and disease. These intersections are where “lived experience” guides the most sophisticated strategies to dismantle multiple facets of colonial rule, with communities and workers designing and building new systems tailored to meet their needs.

Examples:

Tierra Y Libertad – an Indigenous land cooperative in the Pacific Northwest embodies a vision of organizing a solidarity economy that serves to launch other cooperative projects led by Indigenous and migrant farm worker families – creating pathways of resilience for land rights, migrant justice, healthy food, ecosystem restoration and worker coops; breaking the intertwined chains of labor exploitation, border imperialism, white supremacy and environmental racism.[27]

One of the largest urban gardening complexes in the U.S. has been self-organized by Black, working class communities on the frontlines of food insecurity, economic collapse and environmental racism. The Detroit Black Community Food Security Network serves as a space where multiple community farming and food cooperatives and collectives come together to cultivate a transformative vision of change, while training future generations to organize it.[28]

5. Real solutions must advance deep, direct and participatory democracy, rooted in local self-determination.

Real solutions need to be democratically determined and governed locally, involving the collective leadership of communities and workers historically most harmed and impacted by the extractive economy.

While neoliberal policies are based on the ideological premise that corporations have the best interest of people and environment at heart, corporations are actually like machines that will always be guided by their profit-motive. Any real solutions need to be aligned with reining in the power and influence of corporations; eliminating their influence over neoliberal policy arenas that promote false solutions; prioritizing local democratic vision, the essential needs of all peoples, and returning what is owed to those most historically harmed. Over time, we need to build more democratic models of governance that replace present concentrations of wealth and corporate influence with tools that deepen democracy such as participatory budgeting and participatory policy-making.[29]

Like community-owned energy, zero waste and community-supported agriculture,[30], [31] there are many models for economic relocalization that align with deepening and broadening democratic governance and community self-determination.

Women have been cultivating frontline community practices in healing and transformative justice for many decades now, away from police, prisons and other institutions of violence, and towards systems of caring, sharing and healing.

Examples:

Taiwan’s Sunflower student movement led a massive demonstration in 2014, occupying the country’s parliament to prevent their government from signing a new trade deal with China. To activate direct democracy, the students developed an online platform that engaged popular opinion on the streets, and built mass, popular consensus in shaping the services and trade agreement at hand. This hugely successful, grassroots initiative led to further public deliberations that helped shape Taiwan’s nuclear energy policy and constitutional reform.[32]

In the U.S., environmental justice community groups have been organizing to force their local governments to move away from the monopolies of large utility companies and towards community-owned and cooperatively run renewable energy facilities like Sunset Park Solar in Brooklyn, New York.[33]

6. Real solutions must center the leadership and needs of those presently and historically most harmed.

Communities that continue to be first and most harmed by both climate change as well as the economic systems causing climate change are owed a historic debt from those whose growing wealth continues to cause the harm. The genocide of Indigenous Peoples, the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, the femicide of woman leaders by patriarchal religions and the globalized theft of land, labor and lives by colonial empires, have resulted in the massive wealth disparities that exist around the world today. This historic harm has also directly served to create the economic systems driving climate change. Our ability to tackle climate chaos will hinge on how well we are able to repair such harm and redistribute stolen resources to the communities on the frontlines of this crisis.

Fortunately, these communities are often those best equipped to provide leadership, and have been cultivating real solutions by:

- Investing in grassroots, frontline organizing that builds our power, improves conditions in our communities and stops the corporations causing disruption in our backyards;

- Prioritizing localized action to build resilient communities, economic alternatives and infrastructure we need to weather the storms; and,

- Supporting solidarity with grassroots movements around the world, to link struggles and share policies, strategies and resources trans-locally.[34]

These strategic paths allow us to tackle the disproportionate burdens and benefits experienced by historically oppressed communities everywhere.

Examples:

One of the best pathways to simultaneously protect biodiversity, decolonize our economies and mitigate climate chaos is for colonial settler states to give land back to Indigenous Nations and tribal grassroots communities who are best equipped to lead us in restoring natural ecosystems and the elemental balance that will sustain our children in years ahead.[35]

A solution path that emerged with the Movement for Black Lives rising up against police and prison violence across the U.S. is #DefundThePolice, where the bloated budgets of highly-militarized police forces are now being examined in dozens of cities, to see where billions in public funds can be freed up to pay for essential community needs, like health-care, housing and real protection.[36] While led by a long-term vision of police abolition, some local campaigns have taken significant strides in diverting funds, such as in Austin, where money cut from the police budget will be used to convert a hotel to housing for the city’s homeless population.[37]

#Homes4All is a strategy key to unpacking many intersectional avenues to undo systemic oppression and mitigate climate change. One of the most obvious facets being that heating homes consumes a large amount of energy because of reliance on electro-mechanical (active) heating.[38] Examples of passive heating and cooling methods that make intelligent use of building design and materials without using fossil fuels are abundant in many Indigenous and place-based societies,[39] such as the Hogan homes of the Navajo Nation (Dinetah) in the U.S. Southwest,[40] as well as going back millennia to cultures such as the Indus Valley Civilization.[41] Like many Indigenous communities, the encroachment of their lands by coal, uranium mining and other extractive industries has left the Navajo Nation short of housing, water and healthcare, exposing them to disproportionate environmental health impacts from lung disease, asthma, cancer and COVID-19.[42]

Increasingly, societies are becoming aware that tackling the crisis of homelessness first serves as a preventative measure for other poverty-related crises such as mental illness, hunger and addiction. In Finland, the Housing First Program has led the way in reducing homelessness amongst member nations of the European Union by giving permanent housing to the homeless as a first step intervention.[43]

Finally, in seeking to center the leadership and restore the health of those most historically harmed, we need to acknowledge that the destruction of Mother Earth’s complex and beautiful biological systems is directly linked to the femicide, misogyny and patriarchal systems of oppression that women, two-spirited, transgender and gender non-binary people continue to face around the world. If we are to be successful at shaping pathways for future generations to survive this global ecological crisis, we must embrace the leadership of women, two-spirited, trans-gender and gender non-binary people across our movement spaces.

Women have been cultivating frontline community practices in healing and transformative justice for many decades now, away from police, prisons and other institutions of violence, and towards systems of caring, sharing and healing. The Nari Adalats (Women’s Justice Circles) of India are excellent examples of such a move away from carceral and punitive measures to address gender-based violence,[44] and the Berta Caceres International Feminist Organizing School is an inspiring new project cultivating a new leadership to guide a just transition away from the destruction of life and towards a pluralist, feminist economy.[45]

Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa: afsafrica.org

Global Tapestry of Alternatives: globaltapestryofalternatives.org

La Via Campesina: viacampesina.org

Trade Unions for Energy Democracy: unionsforenergydemocracy.org

World March of Women: marchemondiale.org

[1] Delegates to the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit. (1991). The principles of environmental justice (EJ). http://ejnet.org/ej/principles.pdf

[2] Members of the Just Transition Alliance. (1997). Just Transition principles. Retrieved March 11, 2021, from http://jtalliance.org/what-is-just-transition/

[3] Delegates to the Jemez Summit in New Mexico (1996, December). Jemez principles for democractic organizing. https://ejnet.org/ej/jemez.pdf

[4] Members of the Climate Justice Alliance (2016). Ten principles for energy democracy. Climate Justice Alliance. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B0q7QrBgPIoDR1VxVkhRZGdwZUJMSTIxZktIMHB1WjFIWkRF/view

[5] Pinto-Bazurco, J.F. (2020, October 23). Still only one Earth: Lessons from 50 years of UN sustainable development policy brief #4 – The precautionary principle. International Institute for Sustainable Development. https://iisd.org/articles/precautionary-principle

[6] Zero Project. (2014, June 11). Nothing about us without us. Retrieved March 13, 2021, from https://zeroproject.org/nothing-about-us-without-us

[7] Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development. (n.d.). Feminist Participitory Action Research (FPAR). Retrieved March 13, 2021, from https://apwld.org/feminist-participatory-action-research-fpar/

[8] Barefoot College International. (n.d.) Where we work. Retrieved March 13, 2021, from https://barefootcollege.org/about/where-we-work/

[9] Robbins, J. (2018, April 26). Native knowledge: What ecologists are learning from Indigenous people. Yale Environment 360. https://e360.yale.edu/features/native-knowledge-what-ecologists-are-learning-from-indigenous-people

[10] Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa. (n.d.) Campaigning for food sovereignty for climate action. Retrieved March 13, 2021, from https://afsafrica.org/campaigning-for-agroecology-for-climate-action/

[11] Working Group on Indigenous Food Sovereignty. (n.d.). Indigenous Food Sovereignty. Indigenous Foods Systems Network. Retrieved January, 2021 from https://indigenousfoodsystems.org/food-sovereignty

[12] Mingren, W. (2018, January 25). The man who stopped a desert using ancient farming. Ancient Origins. https://ancient-origins.net/history-ancient-traditions/man-who-stopped-desert-using-ancient-farming-009493?fbclid=IwAR0OjDBoz4q-MJLhKBC5oQBe9oP3HDPAEBFabme_AMtmpl5ipfCp74Ghx9I

[13] Simmons, M. (2020, October 15). Skeena sockeye returns jump 50 per cent in three years thanks to Indigenous leadership. The Narwal. https://thenarwhal.ca/bc-skeena-sockeye-returns-2020?fbclid=IwAR1y5V9i9KezwdOE_RTIDwLMJ49HQbYcM2BjpvyNWtPYLuey0YUauwuxIxE

[14] Sherman, D. (2020, June 28). Regenerating the land and Native communities with bison. Provender Alliance. https://provender.org/regenerating-land-and-native-communities-with-bison/

[15] McCarthy, M.I., Ramsey, B., Phillips, J., Redsteer, M.H. (2018). Second state of the carbon cycle report, Chapter 7: Tribal lands. U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://carbon2018.globalchange.gov/chapter/7/

[16] Renick, H. (2020, March 16). Fire, forests, and our lands: An Indigenous ecological perspective. Non-Profit Quarterly. https://nonprofitquarterly.org/fire-forests-and-our-lands-an-indigenous-ecological-perspective/

[17] Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives. (n.d.) How does it work? Retrieved February 13, 2021, from https://zerowasteworld.org/how-does-it-work/

[18] Citizen consumer and civic Action Group. (2020, July). Zero waste manual, a toolkit to establish city and community zero waste systems. https://no-burn.org/zero-waste-city-manual/

[19] Wang, S., & Ge., M. (2019, October 16). Everything you need to know about the fasted-growing source of global emissions: Transport. World Resources Institute. https://wri.org/blog/2019/10/everything-you-need-know-about-fastest-growing-source-global-emissions-transport

[20] TEDCity2.0. (2013, October 14). The walkable city [Video]. TED Talks. https://ted.com/talks/jeff_speck_the_walkable_city

[21] Field, S. (n.d.). Vauban case study: Europe’s vibrant new low car(bon) communities. https://d1trxack2ykyus.cloudfront.net/uploads/2017/10/Vauban..pdf

[22] Mann, E. (2020). L.A.’s “Defund the police” battle: Strategy center’s role. LA Progressive. https://laprogressive.com/the-strategy-center/

[23] About Face (formerly Iraq Veterans Against the War). (n.d.). About face: Veterans against the war. https://aboutfaceveterans.org/

[24] RIPESS. (n.d.). What is social solidarity economy? Retrieved March 20, 2021, from http://ripess.org/what-is-sse/what-is-social-solidarity-economy/?lang=en

[25] Mutual Aid Network. (n.d.) Mutual Aid Networks: Website of the Humans Global Cooperative. https://mutualaidnetwork.org/

[26] Mondragon Corporation. (n.d.). The cooperatives of the Mondragon Corporation. Retrieved March 20, 2021, from https://mondragon-corporation.com/people/en/about-us/

[27] Ussen. (2020, August 6). Cooperativa Tierra Y Libertad. U.S. Solidarity Economy Network. https://ussen.org/2018/08/06/cooperativa-tierra-y-libertad/

[28] Detroit Black Community Food Security Network. (n.d.) About us. Retrieved March 21, 2021, from https://dbcfsn.org/about-us

[29] Participatory Budgeting Project. (n.d.). Mission, history & values. Retrieved March 21, 2021, from https://participatorybudgeting.org/mission/

[30] National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Environmental and Climate Justice Program. (n.d.). Just energy policies and practices action toolkit module 4: Starting community-owned clean energy projects. https://naacp.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Module-4_Starting-Community-Owned-Clean-Energy-Projects_JEP-Action-Toolkit_NAACP.pdf

[31] Right Livelihood Foundation. (n.d.) Seikatsu Club Consumers’ Cooperative. Retrieved March 21, 2021, from https://rightlivelihoodaward.org/laureates/seikatsu-club-consumers-cooperative/

[32] Barry, L. (2016, August 11). VTaiwan: Public participation methods on the cyberpunk frontier of democracy. Civic Hall. https://civichall.org/civicist/vtaiwan-democracy-frontier/

[33] UPROSE. (n.d.) Sunset Park Solar. Retrieved March 21, 2021, from https://uprose.org/sunset-park-solar

[34] Khan Russel, J. (2010, October 24). Open letter to 1Sky from the grassroots. Grist. https://grist.org/article/2010-10-23-open-letter-to-1-sky-from-the-grassroots/

[35] Thompson, C.E. (2020, November 20). Indigenous leaders on the growing ‘landback’ movement and their fight for climate justice. Grist. https://grist.org/fix/indigenous-landback-movement-can-it-help-climate/

[36] The Movement for Black Lives. (n.d.). Defund the police. Retrieved March 22, 2021, from https://m4bl.org/defund-the-police/

[37] McEvoy, J. (2021, January 28). Austin to use money cut from police budget to run hotel for homeless population. Forbes. https://forbes.com/sites/jemimamcevoy/2021/01/28/austin-to-use-money-cut-from-police-budget-to-buy-hotel-for-homeless-population/?sh=305f736f4612

[38] TheyDiffer.com. (2018, February 24). Difference between passive and active solar energy. https://theydiffer.com/difference-between-passive-and-active-solar-energy/

[39] U.S. Department of Energy. (2000, December). Technology fact sheet: Passive solar design. https://nrel.gov/docs/fy01osti/29236.pdf

[40] Bradley, H.G. (1990). Solar Hogan, houses of the future? Dennis R. Holloway Architect. https://dennisrhollowayarchitect.com/NativePeoples.html

[41] Singh, P., Verma, S., & Parveen, S. (2016, January). Critical analysis of passive design techniques employed in Indus Valley Civilization A CASE OF MOHENJO-DARO AND HARAPPA. Architecture, 16(1). https://researchgate.net/publication/326771467_Critical_Analysis_of_Passive_Design_Techniques_employed_in_Indus_Valley_Civilization_A_CASE_OF_MOHENJO-DARO_AND_HARAPPA#fullTextFileContent

[42] Johns, W. (2020, May 13). Life on and off the Navajo Nation – The Nation has one of the country’s highest rates of infection. New York Times. https://nytimes.com/2020/05/13/opinion/sunday/navajo-nation-coronavirus.html

[43] Gray, A. (2018, February 13). Here’s how Finland solved its homelessness problem. World Economic Forum. https://weforum.org/agenda/2018/02/how-finland-solved-homelessness/

[44] Mahila Samakhya Gujarat. (n.d.) The Nari Adalat – Gender justice of the women, for the women, by the women. http://bestpracticesfoundation.org/pdf/PDF3b2-Nari-Adalat-Tool.pdf

[45] Grassroots Global Justice Alliance. (n.d.). The Berta Caceres International Feminist Organizing School. Retrieved March 27, 2021, from https://ggjalliance.org/programs/feminist-organizing-schools/