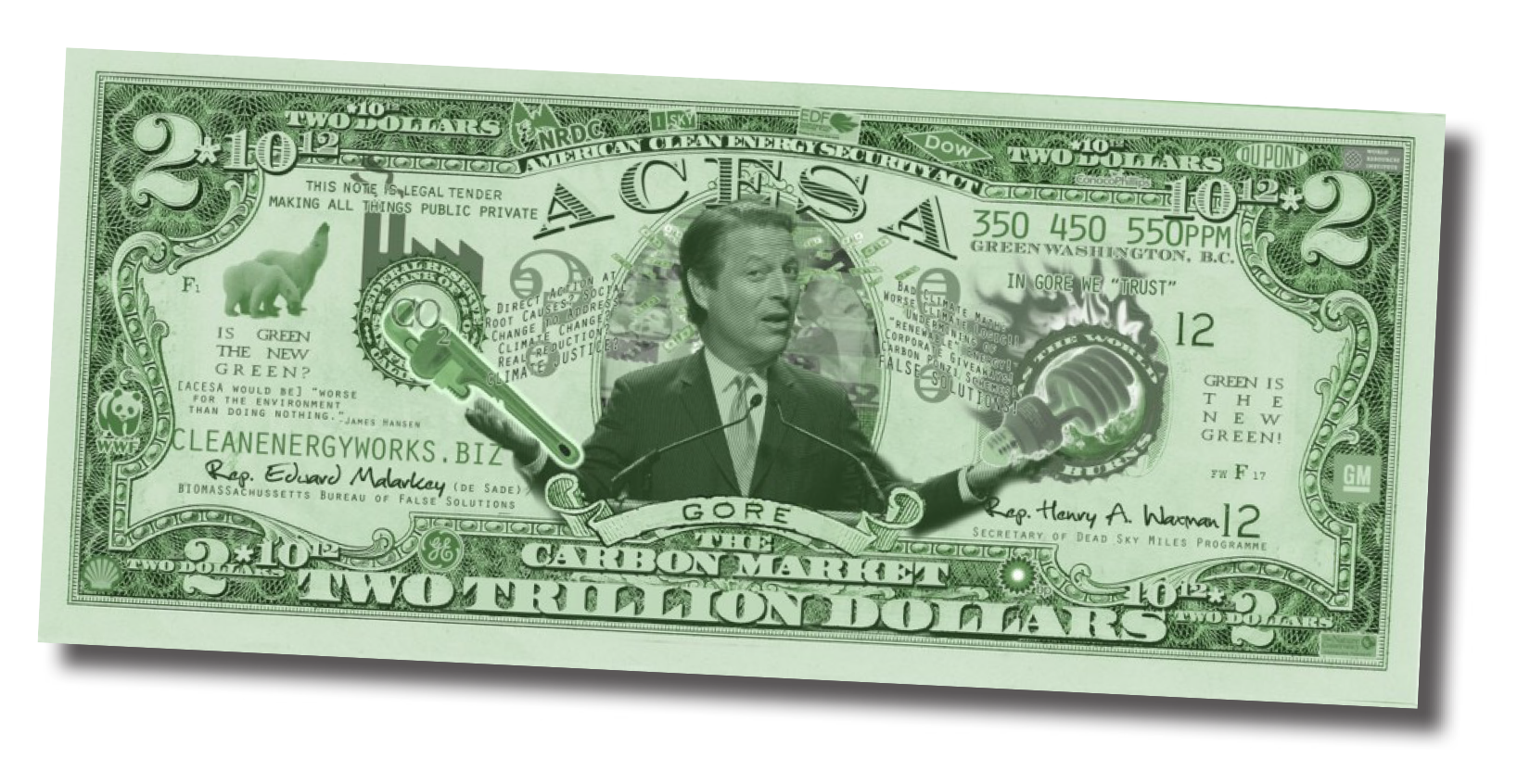

In the last decade, carbon pricing systems have emerged as the primary strategy to address the climate crisis. However, approaches that assign a monetary value to greenhouse gas pollution mask the fact that carbon pricing allows fossil fuel extraction to continue unabated under the false assumption that market forces will drive significant emissions reductions. This section outlines the key carbon pricing mechanisms and demonstrates why they are false solutions to the climate crisis.

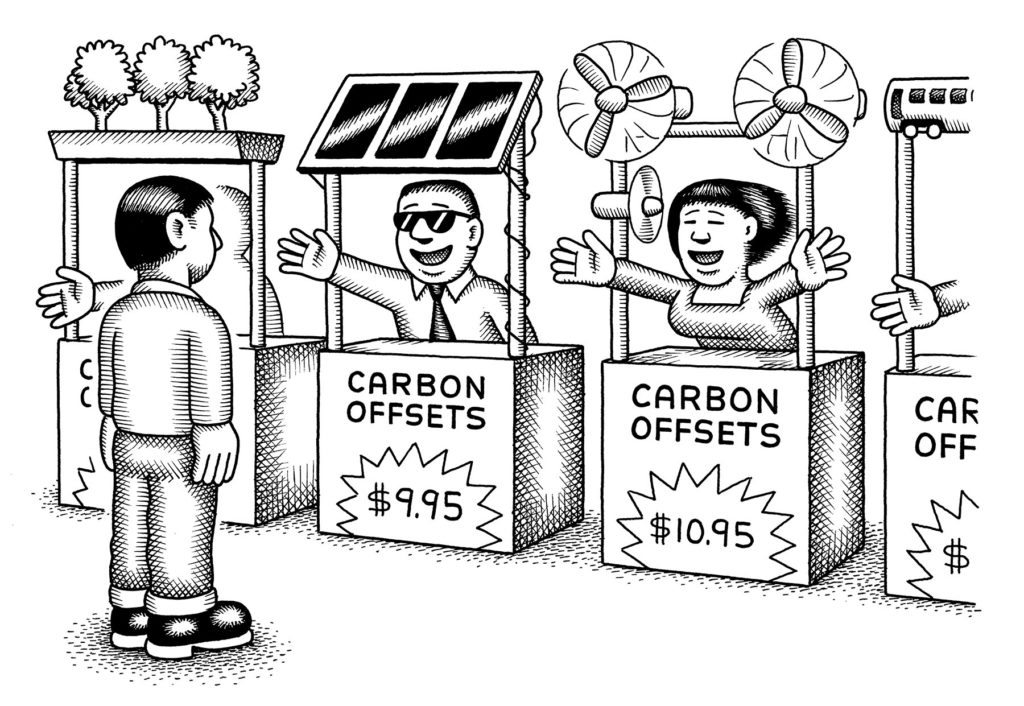

The foundations for global market-based climate policies began with the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. This treaty required developed countries to adopt binding commitments to reduce emissions. However, it allowed these commitments to be achieved through emissions trading systems. Cap and trade systems were promoted under the Kyoto Protocol as a way to limit emissions with a cap and allow corporations to trade permits among themselves, while being regulated by a government. Under a cap and trade system, polluters and investors looking to make a profit can buy, sell and bank allowances given for free or auctioned by the government. Polluters can emit more than their allotted amount (cap) by purchasing allowances from other participants in the market. All cap and trade systems include carbon offsets. Carbon offset credits are generated from projects that claim to reduce emissions somewhere else by doing something else. Offsets are purchased by polluters to justify more pollution.

Cap and trade and offset programs do not directly reduce emissions or fossil fuel use. Instead, they allow industries to keep polluting by paying for more allowances or reductions elsewhere. This results in emissions only being reduced where it is economically viable (if they are reduced at all), leaving pollution to persist in areas disproportionately populated by communities of color and poor communities. Further, carbon markets remain subject to boom and bust cycles. Consistently plagued by low prices, this results in minimal economic incentives for polluters to reduce emissions. Cap and trade and offsets regulated by governments are termed compliance markets, while voluntary markets do not fall under government regulatory structures and are unregulated. These markets are set up by profit-driven private companies and conservation organizations to sell offset credits to consumers, polluters, airlines and corporations.

Carbon offsets are often exploitive and restrict land sovereignty and rights of Indigenous Peoples as well as land access of Black people and other People of Color and low-income communities.[1] Carbon offsets can include destructive large-scale hydroelectric projects, biomass plants, mine methane capture, fuel switching or efficiency projects, so-called “forest management,” animal agriculture methane digesters and many others. Forest and other land-based offsets are particularly problematic because they falsely treat emissions reductions from fossil fuel emissions as equivalent to emissions reductions from land use practices, such as forest management, despite scientific understanding that fossil carbon and land-based carbon are fundamentally different and should not be treated the same.[2] Further problems arise based on distractive accounting measures that implausibly seek to prove that reductions will be permanent and would not have occurred in the absence of the offset program.[3], [4]

Forest offsets do not mean that the timber industry or communities stop cutting down the trees. For example, in the California cap-and-trade system, the often 99-year contracts are signed for “forest management,” which only means a reduction in felling trees. Additionally, the price of carbon itself has remained so low that it cannot compete with high deforestation risk commodities such as soy, palm, timber and fossil fuels. Further, carbon brokers in the voluntary market have increasingly targeted the governmental leadership of Indigenous nations in order to gain access to rights to the carbon on their lands.

In 2007, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the World Bank rolled out the controversial and colonialist scheme, REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation). In 2010, REDD was expanded to REDD+, which purported to include forest conservation, “sustainable forest management” and “enhancement of forest carbon stocks.” A typical REDD+ project offers the promise of economic incentives to a community in the global South, often targeting Indigenous communities with intact forests, in exchange for forest management and selling credits to polluters for the carbon supposedly stored in the forests. Such projects tend to be accompanied by the claim that deforestation happens because too little economic value is placed on intact forests and that providing money for conservation to forested countries in the South will help to protect them while supporting economic development. This assertion has been challenged by many Indigenous Peoples and forest communities, who warn that putting a price on forests has in fact encouraged further land grabs by carbon traders, large companies and governments.[5]

In practice, REDD+ projects tend to follow a divide-and-rule strategy. Communities often find themselves subject to new restrictions on their livelihood activities, new accounting burdens, land grabs and criminalization, while the promised money is often not forthcoming and internal community tensions and divisions increase. Very few communities are even informed that the objective of the contract they have signed is to manufacture pollution rights for faraway industries and business sectors, thus negating any efforts toward consent.

Carbon pricing schemes must be recognized for what they are: unjust and colonial extensions of an oppressive, racist, patriarchal capitalist system.

Another climate change mitigation policy is a carbon tax, or a fee imposed on polluters for emissions they produce. Carbon taxes have not historically deterred industries from polluting, as corporations can easily mitigate the costs by passing on the cost to consumers, cutting workers’ wages, union busting, tax avoidance and lobbying for more subsidies or lawsuit immunity to name a few.[6] Recently, there has been an increased interest in so-called “nested-REDD+” with a carbon tax that allows polluting industries a tax break for investing in REDD+ projects.[7]

Systems such as “carbon fee and dividend” or “cap and invest” are carbon tax schemes that claim to use the funds paid by corporations to provide revenue for climate change mitigation efforts or refund energy consumers. Canada and Switzerland use these schemes. In the U.S., carbon taxes such as these have been pushed on the poor and communities of color with promises of revenue as a way to lobby and gain support for a carbon tax. While enticing, these systems are yet another distraction from moving off fossil fuels because the tax revenue is dependent on continuing pollution and does nothing to stop extraction at source. While Indigenous Peoples struggle against fracking and pipelines and Asian, Black and Latino communities fight against asthma and other health disparities living near petroleum refineries, carbon fee and dividend creates divisions in environmental and climate justice movements because the carbon tax creates a financial dependency mechanism that relies on further pollution with the claim of a payout for certain communities or other projects. The payouts can be in the form of “benefits” that can fund private corporations over communities and ultimately more false solutions.

In an effort to boost the failing carbon markets around 2013, extractive industry and organizations promoting carbon trading began to pursue a rebranding. Around the same time, governments and corporations combined carbon trading, offsets, taxes, REDD+ and other conservation-based trading under the common term carbon pricing, with ambitions to link the various schemes being implemented into a global framework. The 2015 Paris Agreement further solidified this goal by outlining mechanisms for countries to meet emission reduction commitments through linking regional carbon trading systems and other carbon pricing approaches.

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement is the carbon pricing article of the treaty. Article 6 includes two main mechanisms to trade pollution. Article 6.2 is called Cooperative Approaches and allows parties to trade directly without using an international mechanism. Article 6.2 could be used in a situation where national or regional instruments such as the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) are linked with a comparable system in order to create a cross-border carbon market. National and bilateral carbon credit-based systems operated outside the realm of the UNFCCC could also be used under Article 6.2. For example, climate change mitigation activities can be implemented in one country and the emission reduction can be transferred to another country through carbon accounting in what is termed an Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcome (ITMO). The ITMO is then counted towards a country’s emissions reduction target called a Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC). Reductions would include most of the false solutions discussed in Hoodwinked.

Historically, the largest global carbon offset mechanism is the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) set up through the Kyoto Protocol. Article 6.4 is the provision in which the CDM is slated to be converted into the Sustainable Development Mechanism (SDM) in the Paris Agreement. Offsets would again count towards a Party’s NDCs. Questions remain regarding what will happen with existing CDM credits, how the SDM will function and who will be eligible. At the time of writing, it is clear that big business is invited by “offering suitable incentives” to the private sector.[8]

Finally, Article 6.8 is based on non-market based approaches. This section can include dodgy conservation efforts like Payments for Environmental Services (PES) that swap one precious ecosystem for a “conservation” project somewhere else. PES projects often support the expansion of the fossil fuel industries when they are required by the state to implement social or ecological projects through social license to operate (SLO) or by ecological permitting requirements. In these projects an entire region can be destroyed by extractivism in the name of development as long as some project is implemented somewhere else (See Nature-based solutions).

With the architecture of emissions trading in the Paris Agreement still being negotiated, by the end of 2019 the world saw the voluntary markets supersede the compliance markets for the first time. Big business was rife for claiming carbon neutrality in the booming and unregulated voluntary markets. From the major airlines to Microsoft, TC Energy and Amazon, forest offsets, land-based offsets and all the other iterations of carbon pricing took off into a new frontier. Today, dubious, misleading terms including net-zero emission targets, carbon neutral, carbon positive, carbon negative, nature-based solutions (NBS) and carbon capture occupy both policy and corporate-speak alike (see Nature-based Solutions and Carbon Capture). Net-zero emissions, while seeming to imply a state of not producing any carbon emissions, simply means that a business, government or other entity can subtract its total existing emissions on a spreadsheet to equal “zero” with a few stokes of a keyboard and some carbon offsets. But the emissions still exist.

Dangerously, there has been a recent shift to not only monetize carbon as a new environmental service commodity, but to also place nature on an equal plane with technology. Thus, the new wave of climate geoengineering focuses on “carbon dioxide removal,” encompassing unproven technologies like direct air capture and carbon capture and storage/sequestration (CCS) (see Geoengineering and Carbon Capture). To achieve net-zero emissions targets, in addition to carbon capture the focus on removing carbon extends to so-called NBS, which has become the new terminology for land sector carbon. New emissions trading mechanisms are emerging that would provide a platform for the commercialization of now traditional forest-based offsets and extend land sector-based carbon offsets into soils, agriculture and factory farm gas (see Nature-based Solutions).

While the accumulating emissions and ecosystem impacts remain unaddressed by proponents of carbon pricing, the new focus on carbon dioxide removal and NBS is paired with the continuation of traditional yet still very popular forest-based offsets. In that sense, the more things change the more they stay the same, exposing how carbon dioxide removal, “natural climate solutions,” net-zero emissions and NBS are based on the same underlying distraction from extraction. With governments, corporations and NGOs seeking to develop a global carbon market through the linking of national and subnational markets in Article 6, carbon pricing schemes must be recognized for what they are: unjust and colonial extensions of an oppressive, racist, patriarchal capitalist system meant to uphold the status quo and justify land theft to keep fossil fuels coming out of the ground and timber coming out of the forests for the purpose of lining the pockets of the global elite.

Indigenous Environmental Network: ienearth.org, co2colonialism.org

REDD-Monitor: redd-monitor.org

[1] Gilbertson, T. (2017). Carbon pricing: A critical perspective for community resistance. Indigenous Environmental Network and Climate Justice Alliance. https://co2colonialism.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Carbon-Pricing-A-Critical-Perspective-for-Community-Resistance-Online-Version.pdf

[2] Ajani, J. I., Keith, H., Blakers, M., Mackey, B. G., & King, H. P. (2013). Comprehensive carbon stock and flow accounting: a national framework to support climate change mitigation policy. Ecological Economics, 89, 61-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.01.010

[3] Friends of the Earth International. (2021). Chasing carbon unicorns. https://foei.org/resources/publications/chasing-carbon-unicorns-carbon-markets-net-zero-report

[4] McAfee, K. (2016). Green economy and carbon markets for conservation and development: a critical view. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 16(3), 333-353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-015-9295-4

[5] Carbon Trade Watch and Indigenous Environmental Network (2010). No REDD, a reader. https://wrm.org.uy/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/REDDreaderEN.pdf

[6] Irfan, U. (2018, October 18). Exxon is lobbying for a carbon tax. There is, obviously, a catch. Vox. https://vox.com/2018/10/18/17983866/climate-change-exxon-carbon-tax-lawsuit

[7] Gilbertson, T. (2021). Financialization of nature and climate change policy: Implications for mining-impacted Afro-Colombian communities. Community Development Journal, 56(1), 21-38. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsaa052

[8] Personal observation by one of the authors at the UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (COP)25, Madrid, Spain.